Just Call Me Jerry

Story: Katie Wollman '10

Photos: Eva (Lube) Coppinger '17 and courtesy Katie Wollman

Concordia University, Nebraska alumna Katie Wollman conducted a series of interviews with Dr. Jerry Pfabe to learn more about the man who has been a part of Concordia’s community for 55 years.

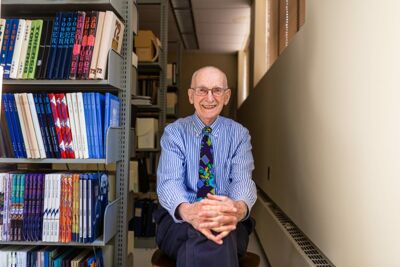

Sometime last year, I watched a video on Facebook, produced by Concordia, on the history of Founders Hall. The video opens on the front steps of the old brick building. It’s a gray, fall day, crisp leaves crowding the sidewalk and just a few bright holdouts clinging to the trees in front. A gentle piano score plays in the background as the clear ring of a bicycle bell sails in; the school’s archivist, Dr. Jerry Pfabe, has just arrived on his bike. He is bundled up in a purple windbreaker, a gray fleece scarf and a navy stocking cap. We hear his voice rise above the music to introduce himself, as he smiles and waves to the camera and tells us that he’ll be showing us around Founders Hall today.

You’d be right to trust him with the task. Throughout his 55 years in Seward, Pfabe, now 83, has been history professor and department chair, Spanish professor and the school’s archivist. He’s taught classes on globalization and the church’s role in society. He’s been an active member at his church, St. John Lutheran. He’s been a town historian, researching and writing numerous articles on Seward’s history. He’s been deemed the “Dean of Noontime Basketball,” competing in faculty basketball games on Fridays until as recently as 2012.

So while he has done far too much at Concordia and in Seward to be known for just one thing, in a way, this is the quintessential portrait of Dr. Pfabe—his lean, lanky figure pedaling leisurely through town on his bike at any time of year, an easy smile on his face.

Dr. Pfabe looms large in my own memories of Concordia. When I came as a freshman in 2006, he was my first formal Spanish teacher as I pursued a Spanish minor, in addition to serving as my advisor. But when I graduated in 2010, I couldn’t have predicted the role that Dr. Pfabe would play as a spiritual mentor and sounding board for me as an adult during some of my shakiest times as a born-and-raised Lutheran.

That’s why, when I learned of his retirement in 2019, I had the inkling to get his story down. A couple of years and a global pandemic later, I emailed Dr. Pfabe last spring with a proposal: to participate in a series of interviews with me to trace his personal and professional history, which I would then offer as an addition to the school’s archives.

Dr. Pfabe responded, as he generally does, within an hour.

“I’m honored that you’re interested in doing this, though I’m not sure I’m worthy of it,” he wrote back. “I’m very willing to go along with your proposal…It should be fun.”

Jerrald Kort Pfabe

Jerrald Kort Pfabe was born to Kort and Henriette Pfabe in South St. Louis on November 23, 1938.

His father worked in quality control at a local automotive company, a job that, according to Pfabe, fit his personality perfectly. “Things had to be done the right way,” he said while describing his dad. “It was almost a triumph for me—maybe I was either in high school or college—when he allowed me to put on the prime coat when he was painting the garage door.”

His mother worked as a beautician for a time, but she spent most of his childhood as a homemaker. “I consider her to be intelligent, kind…I think I gave [her] a lot of trouble at times,” he said, smiling, though he was never “completely fond” of [her] cooking. (This detail he offered bashfully, but unprompted, like he’d been wanting to get it off his chest for a while.)

I’m honored that you’re interested in doing this, though I’m not sure I’m worthy of it.

He attended the local public school for kindergarten through his first semester of 7th grade before transferring to Ascension Lutheran School in St. Louis mid-year. He liked Ascension—he could walk to school and play on the basketball team—but he had to work hard to catch up with his classmates while he learned and memorized the Catechism.

In 1952, he entered Lutheran High School in St. Louis as a freshman. It was there his future plans would shift from what his father had hoped for him—engineering—to what he decided to pursue—teaching. After completing his freshman year of college at St. Paul’s College in Concordia, Missouri, Pfabe transferred to Concordia River Forest, where he studied to be a history teacher. Soon after he transferred, he reconnected with Esther Rehwaldt, who he’d known through mutual high school friends in St. Louis and who had just entered CURF as a freshman. He asked her to homecoming. “She said she was really excited,” he told me. “I think she had a crush on me, and I really didn’t know that.” The pair dated for four years before becoming engaged in the middle of Esther’s senior year. They got married in August of 1961 at Esther’s home church in St. Louis. Two years later, they had twin girls—Rebecca and Susan. Two years after that, they had Kristin.

After college, Pfabe taught for six years at Lutheran High School in St. Louis, where he'd been a student himself not long before. Then, in 1967, at a young 29-years-old, he accepted a job as a history professor at Concordia University in Seward, Nebraska. He and Esther have lived in the same house on Columbia Avenue since they arrived in town 55 years ago.

Pfabe taught a lot of different courses during his time at Concordia, but something that gradually grew to be more important to him was discussing issues of social justice from a Christian perspective. He discussed this especially in his Church and Society course. Twice he and another professor took students in that course to Mexico. The trips focused on understanding the poverty and injustice of people in Latin America and talking to the people there about the root causes of their oppression and how they responded as Christians.

In 1979, Pfabe and his family went on sabbatical leave in Cuernavaca, Mexico, an experience he said was “quite important” to how he saw the world and how he taught on those issues.

As an educator, Pfabe told me, he tried to avoid the idea that teaching was like “filling empty heads.”

“I hoped that I could stretch students’ horizons,” he said. “I tried to be a questioner.”

Absolute Legend

In our second interview, Dr. Pfabe told me a funny story from one of his history classes. The students had spent the whole class discussing several different interpretations of why U.S. Imperialism had happened in the late 1800s. That was how he taught history, Pfabe said, in a way that allowed for different interpretations of the facts. Many of the students were “with it” during the discussion that day, but Pfabe said there was one hold-out. “[At the end of the class] a poor fellow raised his hand and asked [somewhat defiantly], ‘What’s the truth??’”

Dr. Pfabe and I laughed together as he told the story, but, to be honest, I can empathize with the “poor fellow.”

It was the fall of 2018, and I had somewhat recently come out of a difficult season in my faith—a season of doubt. Though I’d landed right side up, I felt disoriented, a little like a stranger in my own land. As I re-engaged with my childhood church after a couple of years away, I was approaching a lifelong relationship with the Lutheran church with new experiences and new questions, and I wasn’t sure if I belonged there anymore.

Spiritually, I was profoundly lonely.

I wrote Dr. Pfabe, outlining my struggles. Looking back, I’m not entirely sure why. It had been years since I’d spoken with him, and I wasn’t even sure he’d be able to put a face to my name.

Twenty minutes later, he replied.

“It was good to hear from you. I thought about you recently, although I do not recall in what context,” he wrote. “Your concerns are important and legitimate, and I take them seriously.”

He did take them seriously; that was evident. Over the next several months, he asked me good, clear questions that were free of judgment. He listened, and he shared his own experience. He was generous with his time and offered his wisdom with humility. His patience encouraged me that, despite the ways I’d changed since being at Concordia, God’s love for me remained the same, and there could still be a home for me in this church body.

Over the summer, I posted an update on the Dr. Pfabe project on Facebook, asking others to share any memories they had of him. The comments came flooding in.

“Dr. Pfabe gave me a bike after mine got stolen. Absolute legend,” one friend wrote.

“He and Esther go to every A Cappella concert, and he always sends an email one or two days later describing something they particularly liked,” Dr. Kurt von Kampen, chair of Concordia’s music department, commented.

“...over the years I knew him more as a friend,” said one former classmate. “We stayed in touch for several years and still do…Thanks for helping me learn Spanish and for being a friend!”

That’s a role that won’t appear on Dr. Pfabe’s resume, or in any official university announcement, but one that’s just as iconic:

To me and to so many others, Dr. Pfabe has been a friend.

Be Faithful

About halfway through our interview project, Dr. Pfabe told me that, as the school’s archivist, there’s a crucial question he must ask himself regularly: “What do I keep and what do I don’t keep?”

As I looked back at my interviews with Dr. Pfabe while writing this story, I got the sense from some of my questions that I wanted him to share some personal epiphanies about himself and how he fit into the Lutheran story. At times, I could recognize the searching on my face, as if his answers might help me make sense of how I fit, and whether or not I still belonged.

Since I wrote that first email to Dr. Pfabe four years ago, we have continued our correspondence, and have tried to stay in semi-regular contact. Sometimes he’ll share the research he’s working on or tell me what his and Esther’s plans for the weekend are; I’ll send him the latest picture of my daughter and he’ll remark how much she looks like me. Recently, he requested that I stop addressing him so formally. “Just call me Jerry,” he said.

In our last interview, I’d naturally saved my most important question for the end. I’d been building to it for some time—four years, maybe. Truthfully, it stumped him a little.

What do you feel is most important to you in terms of your faith, or in your identity as a Lutheran Christian?

Finally, his answer came, and I thought of what he’d said earlier—how it can be tricky, figuring out what you should hold on to and what you can let go of.

“Basically, just try to be faithful,” he said. “Try to love others.”

Thank you, Jerry. I’ll be saving that one for a long time.