In honor of the upcoming Concordia Football Reunion (Sept. 16-17), throughout the summer Concordia athletics will be releasing select excerpts of the book Cultivating Men of Faith and Character, written by Director of Athletic Communications Jake Knabel. The following passage details Jim Wacker, who went on to win four national championships as a collegiate head football coach in the state of Texas. Before earning national prominence, Wacker got his start in the collegiate ranks at Concordia.

Registration for the reunion weekend is open until Aug. 1. To register and/or purchase the reunion DVD and book, click HERE.

-------------------------------------

Ron Harms, inducted into the Concordia Athletic Hall of Fame in 2001, took over as the fifth head football coach in program history in 1964 following a 6-3 season in 1963 under head coach Ralph Starenko. After landing the gig, Harms (then 27 years old) first added to his coaching staff by securing another man with ties to Detroit, Mich., and Valparaiso University – Jim Wacker, a close friend and former college teammate. No one knew it at the time, but both Harms and Wacker were destined to reach legendary status in the state of Texas years down the road. An offensive tackle for Harms, Dean Vieselmeyer stated, “The scuttlebutt amongst all us guys was when we had Ron Harms and Wacker there, we said, ‘they’re so good they’re going to go up the ranks quickly.”

Said Harms of Wacker, “We worked together on a lot of things and he had a very creative mind. We studied the Arkansas monster defense and we put that in. We learned a lot about what we didn’t know. We tried a lot of experiments. Some of them worked and some of them didn’t.” In those days there were classic slugfests between Concordia and Yankton College, which featured future NFL all-pro Lyle Alzado (drafted into the NFL in 1971). Together, Harms and Wacker helped scheme to limit the Yankton star. At the time only a freshman, Alzado was a monster at the line of scrimmage and Concordia’s small offensive line appeared outmatched on paper. Having visited the University of Oregon, Harms came back with blocking techniques that Vieselmeyer described as “bear crawls.” With wider splits, running backs could find holes without requiring mammoth blockers driving opposing defensive linemen up the field.

Alzado was unimpressed by the physically unimposing Concordia group that traveled to Yankton for the final game of the 1968 season. He kidded, “You brought your freshmen team. When are you going to bring out the varsity line?” Said Vieselmeyer, “We were little. I was probably 235. We were really small. Fortunately we had some great coaches and they made use of everything.” On one particular play, Vieselmeyer and tight end Reed Sander collaborated on a double team (one went high, one went low) that barreled Alzado to the ground and sprung a 20-yard run. The play enraged Alzado to the point that he was foaming at the mouth. He responded on the next play by picking Vieselmeyer up underneath the chin and then shaking him. “It’s hard to describe how strong he was,” Vieselmeyer said. “When he set me down I told him, ‘(running back) Jimmy (Widyn) said you were a nice guy. C’mon, you don’t need to choke me.’ That was in the middle of the third quarter and he didn’t hit me hard the rest of the game.” The play lived on in the film room. Wacker rolled it back continuously on the projector as the whole team laughed at an embarrassed Vieselmeyer, who said Alzado had left him with a headache for a week. Chided Wacker, “Hey Viese, what are you doing up there kicking in the air?”

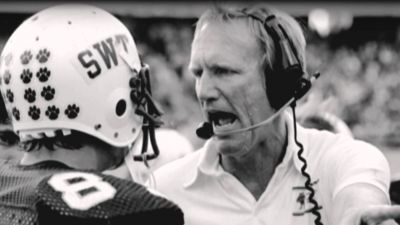

Harms hailed Wacker as a great assistant who worked with enthusiasm. With staffs small in nature at the time, Wacker helped with both offense and defense with a special focus on the offensive and defensive lines and linebackers. For five years, Wacker lent his talents to Concordia before taking time away from coaching to work on a doctorates degree at the University of Nebraska. Wacker first became a head coach at NAIA (now NCAA Division II) Texas Lutheran in 1971 before taking head jobs at North Dakota State (1976-78), Southwest Texas State (1979-82), TCU (1983-91) and finally, Minnesota (1992-96). He won NAIA national titles at Texas Lutheran in 1974 and 1975 and then NCAA Division II national championships at Southwest Texas State in both 1981 and 1982. Through much of the journey, Wacker brought 1967 Concordia graduate Tom Mueller along for the ride. When hired by TCU late in 1982, Wacker was quoted as saying, “I'm 95 percent sure (defensive coordinator) Tom Mueller will come, but he may want to take my job at Southwest Texas. He and I have been together all 12 years I've been coaching. He's the best there is.” Wacker and Mueller were close friends until Wacker’s death on August 26, 2003.

A 1985 Sports Illustrated piece written by the highly-regarded Rick Reilly detailed not only Wacker’s unwavering honesty, but also his colorful personality. In the article, Reilly wrote, “his bizarre weekly coach’s show became such an event on campus (at TCU) that students organized parties to watch it” while adding, “people who know him best will tell you, only half kiddingly, that it’s not just his offensive line that is unbalanced.” The star of the Southwest Conference’s No. 1-viewed coaches show, Wacker brought uncommon honesty to the NCAA Division I level. In 1985 he booted seven players off his TCU team after finding out they had taken “under-the-table” money from alumni. As Mueller recalled, the NCAA told the school that it would go easy on TCU because of its self-reporting of violations that had occurred under the previous coaching staff. It sure didn’t appear that way when the NCAA stripped the football program of 35 scholarships.

Some coaches around NCAA Division I surely felt Wacker was honest to a fault. There was little doubt he was a man of great character. At the age of 66, Wacker died of complications caused by cancer in 2003. On his death bed, Wacker remained as positive as ever. In a memorial newspaper account of the time, Mueller was quoted as saying, “One of the last things he told me was to enjoy my kids, because life is all about relationships. Even as he was dying, he was encouraging people as we were encouraging him.” Added Mueller in that same piece, “He had a very contagious personality and a zest for life. He was always an optimist and looked for the good in everyone.”

Prior to becoming a beloved Texas figure and the subject of Sports Illustrated pieces, Wacker got his first collegiate coaching job at Concordia. During his time in Seward, the Indiana native also served as head coach for the wrestling and tennis programs. Formerly known as Southwest Texas State, Texas State named its home field after Wacker in 2003. Simply put, he was a legend who mastered the art of turning around programs that had experienced little success. The Frogs had been accustomed to sinking to the bottom of the barrel in the old Southwest Conference. By year two, Wacker had Fort Worth buzzing as TCU jumped into the top 10 of the national rankings in 1984 and finished the season with a berth in the Bluebonnet Bowl.

It always seemed like Wacker knew exactly which buttons to push. As 1966 Concordia graduate Dennis Oetting said of Wacker, “he could make a rock get up and walk.” Coming off back-to-back national championship seasons at Southwest Texas State, Wacker inherited a rebuilding job at TCU in 1983. At the conclusion of a 1-8-2 first year with the Frogs, Wacker decided to literally bury the season. Wacker memorialized the season by bringing a casket to midfield. With everyone dressed in black suits, Wacker “prayed that the season was over,” remembered Mueller. Wacker had a knack for getting everyone involved. He willingly accepted fans and media into the locker room after games. Said Mueller, “win or lose, the cameras were on.” Wacker encouraged his players to enjoy success. Following wins, the postgame locker room celebrations were particularly joyous. It just fit Wacker’s personality. In a phone interview, Mueller described Wacker as someone who “came to work every day fired up and excited. He would not let you get down in the dumps. He was gung ho in everything he did, including the way he loved the Lord.”

Few knew and understood Wacker in the way that Mueller did. Mueller enjoyed an impressive coaching career in his own right. As defensive coordinator, his 1974 Texas Lutheran unit pitched six shutouts and held opponents to averages of 172.5 yards and 4.0 points per game. So sharp was Mueller that Wacker described him as “one of the truly bright defensive minds in the country.” Their close relationship made their parting following a 7-4 season in 1991 at TCU particularly difficult. Just as the program seemed to have recovered from the NCAA’s severe punishments, administration decided to turn down a bowl game invitation. This was at a time when only 18 bowl games existed. No one turned down bowl games. As a result, Wacker decided to leave for the head job at the University of Minnesota.

Most of Wacker’s staff followed to Minneapolis, but Mueller could not pull the trigger. He had children enrolled at TCU. The family did not want to leave Fort Worth. “There were tears in everyone’s eyes,” Mueller said of one of the staff’s final meetings together. “I was crying like crazy. Everyone was going to Minnesota. It was tough.” All along, it seemed like God meant for Mueller and Wacker to coach together. As a child, Mueller remembered first seeing Wacker at a wedding reception. It was the wedding of Mueller’s cousin, who roomed with Wacker at Valparaiso. Somehow the face and stature of Wacker stuck in Mueller’s memory. As a sophomore linebacker at Concordia, Mueller saw the man he remembered from the wedding in the school newspaper. Wacker had agreed to become defensive coordinator at Concordia. Of course Wacker did not recall the middle school boy that he’d made an impression upon several years earlier. Standing in line for equipment in the preseason, Mueller reminded Wacker of their first meeting. Remembering what a ‘good time’ he had enjoyed at the wedding, all Wacker could say was, “Oh no.”

In all, Wacker and Mueller spent 21 seasons coaching together. An entire book could be written on that period alone. Some of Mueller’s fondest recollections go beyond the four national titles and the high of turning around what had been a Southwest Conference doormat. Mueller makes a point of reciting valuable lessons delivered by Wacker to his teams. One of his favorite sayings was: “do the things you know to be right and refuse to do the things you know to be wrong.” Before games he would tell his players: “do your best. Don’t sweat the rest.” In most obvious ways, the relationship between Mueller and Wacker was mutually beneficial. “All I ever wanted to do was be a football coach,” Mueller said. “It was a great experience to be with Coach Harms, Coach (Ralph) Starenko and Coach Wacker. Coach Wacker told me he would call me about a spot on his staff when he got his first head coaching job. I didn’t think it would ever happen for me. It’s been special. I’ve had to pinch myself at times.” Having been out of coaching for eight years, Mueller returned to the sidelines as head coach at Texas Lutheran in 2002. He did so at the urging of and with the support of Wacker. Said Mueller of his coaching run that finally ended in 2007, “It was a lot of fun.”

Wacker’s final season as on the sidelines came in 1996. His overall record as a head coach was 160-130-3. He was named National Coach of the Year by the Sporting News in 1984. Many remembered Wacker more for his character off the field. Said Texas Lutheran athletic director Bill Miller shortly after Wacker’s death, “(Jim) had character and integrity that is incredibly rare. The way he led his life is an example for everyone to follow. In a day and age when people are winning at all costs, Coach Wacker was determined to win the right way.”